Intro

At business school, an important skill we learn is how to value companies. We learn the basics of constructing DCFs, the important information we need from financial statements, and how to use past data to make sense of new ones. However, our professors rarely (Prof. Damodaran is an exception) bring up the biases that impact decisions we make in valuing different deals. Moreover, we come out of business school without a strong sense of how our different personalities, experiences, and humanity may impact our investment decisions later in life, whether in a professional setting or just in our own portfolios. In this blog post, I will explore the decision-making process of valuing venture capital deals as holistically as possible, both in terms of the numbers and the inherent psychology. Investing is not as objective as we may want it to be.

Part 1: The Numbers

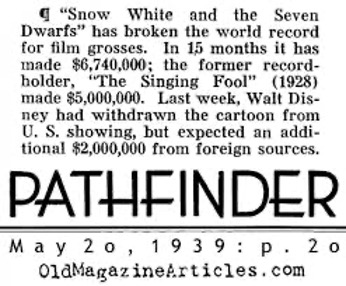

Venture capital in some ways is a game of chance where tail events drive most, if not all, of a fund’s success. Similar to how 83 minutes of Snow White made Disney successful, 1 or 2 amazing deals in a fund typically drive all of its returns. Thus, sourcing deals and distinguishing bad ones from good ones is of utmost importance.

Inbound sourcing relies on entrepreneur networks, fellow VCs, angel investors, and cold inbound communications from founders. Here, it is important to keep in mind that the cold emails funds get from founders, for example, may have negative selection bias. The best founders wait for funds to reach out to them rather than doing extensive marketing themselves. Outbound sourcing, on the other hand, relies on reaching out to specific companies, general networking, and focused networking at demo days, conferences, and other events. The best strategy for sourcing relies on a combination of inbound and outbound to identify the highest potential startups.

One of the most effective ways to find great startups is to start broad and then narrow it down. Take fintech for example. It is a big field and a rather new field with a few large players and many small players. When researching the industry, start by reading articles on Pitchbook to select the main sub-sectors in the industry that are predicted to grow the most in the next 5-10 years. One of these sub-sectors is embedded finance. Now, an analyst can look through portfolios of angel investors and other VC funds to find startups that are in the sub-sector and match their fund’s criteria. Thus, one has successfully narrowed down from a broad industry to a series of startups in a sub-sector that one has some knowledge about that can help in later outbound reach outs and conversations with entrepreneurs.

In a typical deal memo, analysts will pick valuable information from a startup’s pitch deck and data room to analyze and reach a preliminary opinion. These include the company’s pre-money valuation, amount raised, cap table etc. However, before writing a memo, how do venture capitalists evaluate the credibility of a startup and of its founder/s? Are decisions to proceed to the next step sometimes based on instincts?

Part 2: The Psychology

Psychology plays a major role in any profession where decisions must be made. Even though finance and investing can be mapped out by algorithms and now artificial intelligence, the actual decisions we make are skewed by our intentions and instincts. Venture capital is no different. From the basic guidelines for VCs to succeed to deciding to trust certain founders, VC decisions are heavily driven by psychology.

To succeed VCs need to focus on three major factors, one driven by the next: maintaining good relationships, taking sizable ownership in their companies and being part of large exits. Along the way, there are two main psychological drivers: Fear of Missing Out (FOMO) and Fear of Looking Stupid (FOLS). Every VC likes big wins, so deals that get away come with deep personal regret that impacts your later decisions. When you see another company that could be a big success, with a strong team, and in a field that you like with a good idea, it is tough for you to not invest and make the mistake you made before. “I told you so” is a phrase that fund managers do not want to hear. To avoid this, VCs tend to not invest in companies that compete with very successful companies, not invest in a field where a top fund has already invested in a competitor etc. To put it simply, VCs tend not to invest anywhere where they can potentially end up looking like the underdog. Balancing the dichotomy between FOMO and FOLS is the realistic story that drives VC decisions. With the need to screen hundreds of companies and choose the winners that can turn into huge companies, VCs constantly try to find a very safe deal at the low price of a very risky deal. This mindset also drives the way fund analysts screen founders during first and second meetings.

VC meetings with entrepreneurs are not unlike interviews with candidates for a job. There is an element of seeing if the entrepreneur’s company “checks all of the boxes” in technical aspects and just as importantly, venture capitalists use these short meetings to assess the founder’s personality and trustworthiness. This assessment is often based on gut feeling.

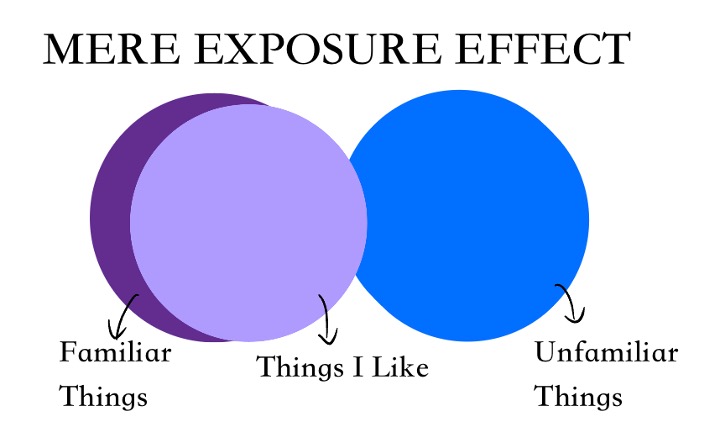

A 2018 paper published by two Swedish researchers sought to analyze the personalities of entrepreneurs for an artificial intelligence application. They interviewed venture capitalists and entrepreneurs in Sweden and Iceland and found that there are multiple innate issues that may hurt the decisions venture capitalists make. First, the Mere Exposure Effect, the psychological phenomenon of people developing a preference for people/things more familiar to them than others, shapes the way VCs evaluate entrepreneurs. For example, a venture capitalist may, subconsciously, prefer founders that have similar backgrounds to themselves or simply have a greater sympathy for founders that look physically like themselves.

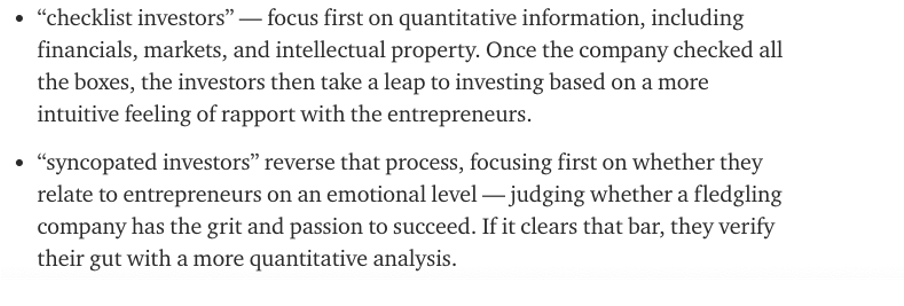

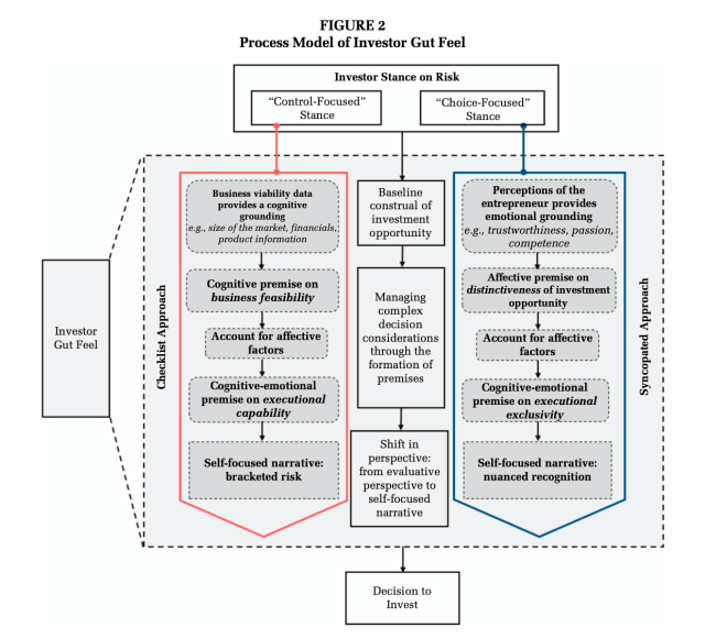

Second, many founders that were interviewed do not have and do not know how to have a balance between thinking fast and thinking slow. Daniel Kahneman’s award-winning book Thinking Fast and Slow draws the distinction between system 1 which operates automatically and quickly to system 2 which allocates attention to the effortful mental activities that demand it. Harvard graduate Laura Huang’s paper in the Academy of Management Journal builds on to Kahneman’s points through her analysis of 100 interviews with investors where she found they largely fall into two groups: “checklist investors” and “syncopated investors”. These studies taken together showed that venture capitalists often don’t have a grasp on when to oscillate between systems 1 and 2, which drives irrational decisions that are difficult to rationalize later on.

Part 3: Tying it All Together

Knowing that venture capital decisions are driven as much by numbers as by psychology, what are the implications for startup founders? To begin, it is important to realize that it is not enough for founders to be armed with compelling research and numbers that check all the boxes. After all, a VC’s investment in a startup and relationship remain for years and not mere weeks or months. Thus, entrepreneurs must appeal to the brain, the heart, and the gut of founders to cover all their bases. Like candidate interviews, entrepreneurs should have both the ‘hard facts’ such as a strong IP and market research but also develop a chemistry or relationship with the venture capitalist. Now that artificial intelligence such as Hirevue software are implemented in screening processes, there is the potential for decisions to be less biased and less personal than before.

It is also important for everyone – entrepreneurs and investors alike – to realize that venture capital and investing in general is a very new field. Most start-ups do not achieve the success they dream of and in a parallel fashion most VC investments tank. Napoleon’s definition of a military genius was “the man who can do the average thing when all those around him are going crazy”. It’s the same for VC decision making and investing in general. Make guidelines for when to think logically and when to trust your instincts, thus playing to the strengths of human decision making.

Sources

“The Psychology of Money” – Morgan Housel

The Personality Venture Capitalists Look For in an Entrepreneur – Brandt and Stefánsson

The Role of Gut Feeling in VC – Eze Vidra from Remagine Ventures

The Undoing Project – Kahneman, Tversky

Laura Huang’s Interview with HBR

How VCs Think – Nfx